SWIFT's King of The Hill Experience

- 13 minsDuring October, I saw that SWIFT was hosting a competition called King of the Hill, or KoTH for short. I decided to join in with a few buddies of mine with an alias of Jake Kim from Lookism. It was very interesting; here are my experiences.

What is King of The Hill?

KoTH is a multiplayer cybersecurity game that blends in a mix of offense and defense. Multiple teams attack a single network of vulnerable machines that contain various weaknesses and misconfigurations in regards to things like initial access and privilege escalation. Machines also contain files known as “flags”. These flags are located throughout the machine in the form of a text file called flag.txt, usually one for the user account, one for root, and a few for specific services. For example, for web services, the flag would usually be located in the /flag page, while the FTP server can have a flag.txt within the FTP root. Once players gain access and escalate privileges within a machine, players must edit the flag.txt files with their team number in order to gain points for their. However, other players will try to edit this flag as well, so the team must prevent others from changing this flag by applying security patches, changing passwords, and other hardening techniques to secure the machine.

Preparation

As an alumni with a good amount of CCDC/CPTC experience, as well as current Red Team knowledge, I thought this would be a pretty fun competition to be a part of. I joined in with a few buddies of mine and we started prepping for the event.

About a week before the competition, I had spent a few hours per day coming up with different strategies and techniques related to persistence and making sure that other players aren’t able to edit flags. I wasn’t too worried with the pentesting side of things, as I was pretty confident that I could figure out how to get root or SYSTEM on a machine.

I created a Google Sheets that contained a massive checklist of different commands to run for different persistence techniques. For example, I had commands for creating an SSH key, creating a new user, modifying scheduled tasks, and more. I was also planning to run Mythic C2 so I needed these commands to be one-liners so that I can run them from a beacon. I had also planned to not abuse firewalls to give other teams an opportunity to obtain initial access on the machines, but I still had quick firewall commands just in case.

Once we were finally added to the competition Discord server, I was able to see who my competition was. To my dismay I saw that Team 4 had:

- Brice, an OSCP-certified monster and one of the smartest guys I’ve worked with ever in SWIFT and CCDC.

- Gabe, a Linux beast who I worked with in SWIFT, CCDC and even won globals in CPTC with.

- Sohee, a student from Fullerton College who graduated early from one of the top CyberPatriot high schools in the nation and super well-versed in offensive security.

It was definitely going to be a challenge and I knew that I had to try a bit harder in this game and ended up deciding to incorporate firewalling into my strategy.

The Competition

On the day of the competition, I saw even worse news. There was another team, Team 12, that had equally, if not more, insanely smart people - 2 CyberPatriot national champions and 2 OSCP-certified folks. Jeez.

Once the competition environment opened, I saw that half of the machines in the environment were returning boxes from the practice round a few days prior, which I had attended and therefore had prior knowledge of the vulnerabilities for some of those machines. One of those machines was a Windows Server box that contained a DotNetNuke web server. We were able to really quickly gain remote code execution on the system by exploiting CVE-2017-9822, a cookie deserialization vulnerability, and since our current user context contained SeImpersonate privileges, we were able to gain SYSTEM through Juicy Potato. We then secured the machine very quickly and took control of the user and root flags, as well as completely locked down the system with the use of Windows Advanced Firewall.

However, there was also a flag that was stored on the web server at /flag. I thought the flag would be a simple file on disk to edit, but it turns out that DotNetNuke stores that kind of data in a MSSQL server. What I ended up doing was enabling and connecting to the machine via RDP, authenticating locally to MSSQL server through cleartext creds that were discovered in a web.config file, creating a new user on DotNetNuke web page, and then making my newly-created user a “super user”, which allowed my user to make changes on the website. Once I did that, I was able to log into the DotNetNuke admin interface and edit the /flag web page through the web browser.

The Battle over the Missile

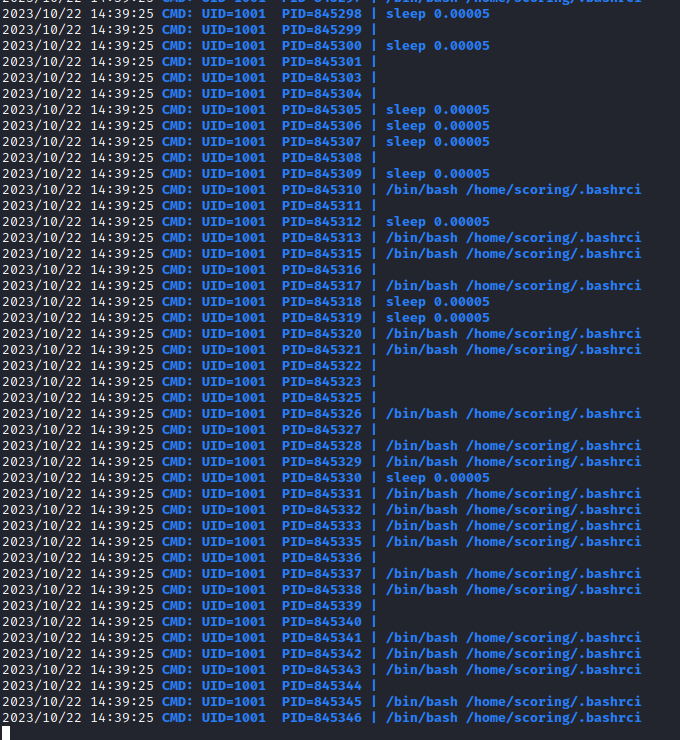

Once the Windows box was locked down, I moved onto a Linux box called “Missile”. This contained a Python Flask application with a Werkzeug debug page that allowed for Python code execution. This allowed us to obtain a reverse shell onto the machine as an unprivileged user, which contained a flag within its home directory. I was not able to get root but I was able to modify this user’s flag, which allowed us to get some points from the machine. It turns out that Teams 4 and 12 were getting onto this machine as well and were modifying the flag, so it kind of became a battleground between the 3 teams. I don’t think they were able to get root either, since most of the activity was from the unprivileged user. I didn’t see much action from Team 4 but Team 12 was noisy as heck. They made a function that would run a file called .bashrci in the scoring user’s home directory every 0.00005 seconds. This .bashrci file was a simple Bash script that echoed their team number into the flag. I was only able to discover this by running pspy.

It was a bit excessive in terms of hardening the machine, but it was kind of funny to see and definitely a creative way to ensure flag persistence. I had removed this .bashrci file several times, and Team 12 would keep replacing the .bashrci file every few minutes or so. I don’t know if Team 12 had a scheduled script but it had meant I had to continuously monitor this box and this flag. However, I had my own sneaky ways of writing into this flag file, which allowed our team to get the majority of this flag’s points.

I didn’t focus on the rest of the machines, either since they were locked down by either Team 4 or 12, and that I was too lazy to focus on the other machines.

The Results

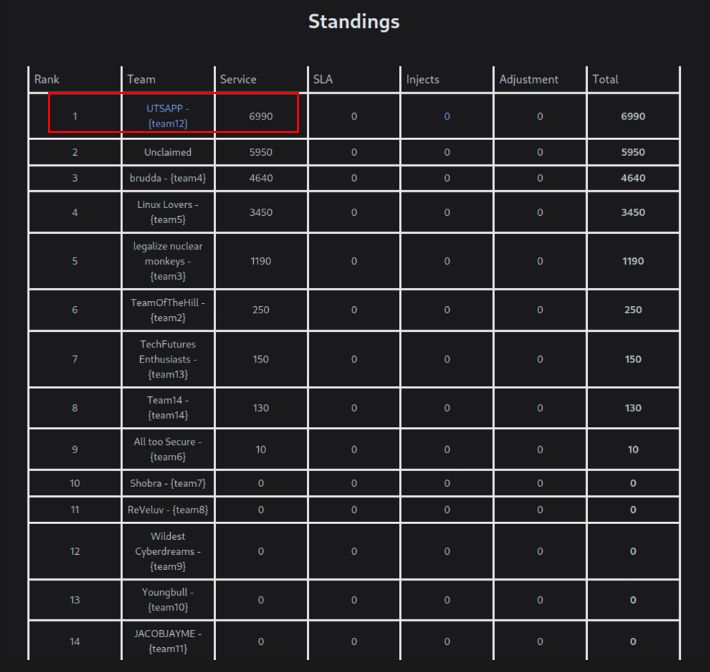

Team 12 won by a huge margin with 6990 points. Not going to lie, they were definitely prepared (they had obtained several flags within about 30 seconds into the competition) so it was pretty clear who the victor was. Team 4 came in at second place with 4640 points, and Team 5 (our team) came in at a solid third place with 3450 points. The score distribution drops down pretty heavily for the other teams, with most teams scoring under 300 points. Below is a screenshot from the first place winner, hence the red box.

Lessons Learned and Feedback

Overall I think the event was OK. The core gameplay worked and scoring worked for the most part, but the game didn’t feel polished and the competition was heavily skewed towards the more advanced players.

Still I need to give credit where credit is due. Major props to the entire dev team for making this event possible. I’ve heard that the servers and infrastructure that was hosting the game went kablooey, ending up in some all-nighters to fix the environment. The machines were also created by students learning about cyber, so honestly it’s kind of expected that the game will run into lots of issues, but I still think it’s a good experience for both the dev team and the competitors.

One of the biggest issues I had was the lack of testing and quality assurance. For the DotNetNuke box, I felt like the assumed path for the web flag seemed to be simply editing a file on disk somewhere within the web root, but in actuality the contents were stored in the MSSQL database and the way to edit that was way more convoluted. Seeing how this competition was mostly targeted towards beginners, I don’t think this was the intended path to control the web flag. Furthermore, my Kali VM was connected to the environment’s network through VPN, and my IP kept changing every few minutes. It was impossible to set up a C2 because of that.

Besides the technical issues, given the nature of this game, it’s definitely more geared towards intermediate players who have enough technical ability to plan strategy and actually play the game as it was intended. I think the majority of the players had very little experience in cyber. I can see how it can be a bit unfair for a team full of CyberPatriot 1st place champions to go against students that are new to Linux.

As for my buddies on my team, it was definitely very tough to explain my methodologies and strategy since they were new to things like port scanning and externally-facing services. I did my best and tried to walk them through the DotNetNuke attack path, from initial access to SYSTEM, along with creating a new admin user as persistence, but it’s hard to say if the understanding went through.

At the end of the day it’s a skill issue.

I think there has to be some rules to give those newer players at least a chance against the machines. TryHackMe has a KotH game and in this blog post they explain the rules pretty well. One of the things the blog mentions is that “its not a fight if there is no one in the ring”. Things like aggressive firewalling, completely patching up systems, abusing killing sessions, etc. should probably not be allowed since it completely destroys the chance that another team can get onto the system.

When I was doing chest day with Palmer, a SWIFT eboard member who is also a very buff dude, we chatted about KoTH and he mentioned having two separate brackets for competitors, which I think can be interesting. It can make for a more even-level playing field, since the greener folks don’t have to worry about an instant lockdown of boxes. However, in the upper bracket, the issues with completely locking down systems still exists. If a team manages to get root first, they can instantly disable all initial access vectors and completely own that box, preventing other players from even touching that box.

One suggestion I have is disabling access to root or SYSTEM entirely from all of the machines. This was the situation that Team 12 and my team were in on the Linux machine, where we didn’t have the permissions to enable firewalls or disable services, but still had some leverage over the machine to modify flags and monitor processes. We had to resort to really cheeky and creative ways to control the flags and prevent others from capturing our flags. I think this made for a really interesting battleground and definitely was the better part of the competition. The machines can have another unprivileged user with a “root” flag to simulate some sort of privilege escalation.

Preparation Tips

I mean this is a little bit tough from a beginner’s standpoint since it assumes that you are super comfortable with the pen testing lifecycle, as well as understanding how to harden a Windows/Linux box. Not just general things like “enable the firewall to allow services in” but specifically “what are the exact commands to enable SSH traffic inbound from only my host”. For initial access it definitely helps to do things like HackTheBox and understand common vectors to gain a foothold. I had only known about the DotNetNuke exploit because I skimmed over the Tuesday meeting slides, which mentioned DotNetNuke somewhere.

You also have to do these things very, very quickly.

While lots of the trivia can be learned through things like HackTheBox or TryHackMe, situational awareness and troubleshooting are tough to learn. For example, when do I know when to run a gobuster scan? Or when do I know when to run Juicy Potato exploits to gain SYSTEM? It all comes down to 1) what your current access is, 2) what information/access you are trying to gain, and 3) what things can you run with your current permissions. This is something you mainly only gain from continuous exposure to situations where your decision-making abilities are tested. With intentional and mindful practice, your decision-making skills will improve and your intuition will expand over time. You will eventually get to a point where you will be comfortable with solving difficult problems.

The way I practiced was doing research on persistence techniques and trying out those different techniques on a homelab of sorts. I had spun up a Windows Server 2019, an Ubuntu 20.04, and a Kali machine. Each time I would test out a technique, I would evaluate what sort of impact on the system it had, what permissions it required, if it made it harder for other players to do stuff on the machine, etc.

I think this is a really good practice method. The cycle of doing your own research, trying out a specific technique, looking at the results, and evaluating whether this is a good strategy or not forces you to set up an environment, come up with new ideas, troubleshoot, and document your findings, something that resources like TryHackMe can’t offer. I mean this is literally how top teams prep for competitions like CCDC and CPTC. Yeah, there’s definitely a good amount of knowledge required to figure out what to research in the first place, but this high learning curve and immense dedication to the grind is what separates the good from the exceptional.

Do difficult things and make deliberate efforts to learn. You will be surprised on how much you can accomplish.